Communities-of-communities

Back Garden Biennale 2016, part of Leith Late and Annuale from Embassy Gallery, celebrating contemporary visual arts and artists in Edinburgh, took place at a 53 Elm Row on Leith Walk, 23-26 June 2016. An essay ‘Communities-of-communities’ was written by academic Deborah Jackson.

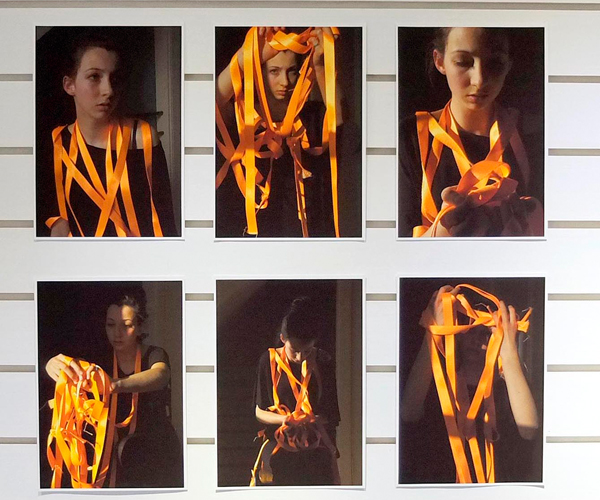

Artists: Sarah Dale, Laura Davis, Sally Hackett & Mariella Verkerk, Pinaach Kolte, Daniel Killeen, Chloe Milner, Sara Monaghan, Emily Moore, Camila Richardson, Margit Schranner and Jasmin Sutherland

Supported by Pack & Send, Leith Late, Creative Scotland, Place & Platform and Settlement Projects

Street sign, Leith Walk

Communities-of-communities

Deborah Jackson

When it was launched a decade ago in 2006 the Back Garden Biennale (BGB) was very much targeted at a domestic audience, staged as it was in Sara Monaghan’s shared tenement back garden in Edinburgh’s Blackford area. At this time Monaghan was at the midpoint of her MFA at Edinburgh College of Art and she initiated the BGB as an extension of her art practice, which occupies a number of platforms including maker, curator, facilitator, and performer. Notably, underpinning all of Monaghan’s art practice is the aim of building social bonds through communal meaning and activity and the BGB visibly focuses this purpose. With the intention of fostering the informal networks of which she is part, Monaghan invited twenty artists drawn from her circle of artist friends to participate in the inaugural event. In its next iteration in 2008 the BGB relocated to Monaghan’s new address in her suburban back garden in the Fairmilehead area of Edinburgh. Then in 2010 the BGB went on holiday to North Uist in the Western Isles of Scotland. The BGB returned home to Fairmilehead for 2012 as part of the Annuale (est. 2004), the annual festival of independent and grassroots artistic activity in Edinburgh co-ordinated by the Embassy gallery. This year, in 2016, after a respite in 2014, the BGB has resurfaced in Leith as part of LeithLate (est. 2011), the grassroots visual arts organisation initiated by Morvern Cunningham. The BGB ’16 is located in the communal garden of The Basement Art Club (est.2015), an art space organised by Maya Glaspie with “the aim to promote local artist and join them with their community”. Key here is that the BGB, Annuale, LeithLate, and The Basement Art Club are all self-organised artist-run initiatives that are founded on the basis of connecting communities through art.

The BGB is a contemporary, non-profit independent visual arts biennale that shares the Annuale’s particular ambition to reconceptualise what biennales represent to the communities involved. To its critics the international biennale phenomenon’s status, exemplified by the Venice Biennal, has come to signify an over-blown symptom of spectacular event culture. Such events are considered to be little more than entertaining or commercially driven showcases designed to feed an ever-expanding tourist industry. However, from its inception the BGB, as a self-organised initiative, was clearly not competing for the attention of the global (art) tourists who generally flock towards the crass commercialisation and populist approaches of large-scale art exhibitions. Instead the BGB sought to explore an alternative route to developing an art practice outside, alongside, within, and beyond that of the established artworld. The BGB follows in Edinburgh’s long tradition of artist-run, self-organised initiatives that offer a means of challenging the dominant order and that have continually found new ways of doing things without relying on established institutions or large sums of money.

Indeed, through self-organised and communal strategies of participation and organisation it was Monaghan’s aim “to create an art event for the community in the community”. Given Monaghan’s statement of intent and the somewhat nomadic nature of the project the idea of communities emerges as a context within which to consider the BGB. However, the value of this approach depends on rethinking the term and looking at communities as forms of relationships. In other words communities are constructed symbolically and are not necessarily based on locality. This view also serves to highlight the possibilities for diverse forms of belonging and acknowledges that different configurations of groups of people and their boundaries can be overlapping and that communities can be episodic and situationally determined.

Equal attention is required towards ideas around self-organisation, which dovetails with those of community, given that self-organising is rooted in a desire to shape communities where people share skills and endeavours. Historically self-organisation within art practice is related to institutional critique and also to the legacies of anti-establishment and counter-cultural practices. However, whilst contemporary artists who self-organise may not be viewed as overtly political or social dissidents it can be argued that the artist is always an agent for social change whether they consider their practice socially engaged, socially concerned or indifferent to socio-political issues. Whatever the position artists take the overarching point is that art activity is, perhaps now more than ever, inherently tied to the changes in the communities of our social landscapes.

Understanding community can be a difficult task as it is a construct that can be viewed through many different lenses. In the first instance we can perhaps begin to define communities as being established and understood on the basis of shared activities and goals, as an active and self-conscious process. This is not to suggest communities are static, they are in constant flux, they are centred on a set of shared social meanings which are constantly created and mutated through the actions of its members, and through their interactions with wider society. Most prominently since the late 1960s the term community has been central to the development of particular strands of activism which have been concerned with decentralisation or self-determination. It is within this range of grassroots social and political activism with a commitment to an economy of mutual aid and cooperation that we can identify a correlation with forms of agency such as initiating, organising, curating, and exhibiting. When you consider that art and exhibitions are systems for disseminating ideas then it is no surprise that artists actively engage with the means by which their art is mediated by controlling the systems and environment that it and they inhabit. From a practical or pragmatic position, organising through self-organised actions with contemporaries is often aimed at providing the resources for showing work, which an individual artist may struggle to access alone. It is therefore worth contemplating the substantive responsibility involved in curating the BGB as a self-organised initiative. Of relevance here is the selection process in that it is just as much the artists as the artworks that are programmed.

Whilst particular artworks are selected for inclusion, opportunities are often given based on an affinity with an artists’ previous work, in other words the artist is trusted to create new works of art, albeit on a no or low budget basis. So clearly it’s not just about outcomes it is also about process. It’s about participating and the voluntary nature of participation that is dependent on self-motivated and self-generating practices. In this sense the BGB can be seen as a way to emphasize that every practice is dependent on the social processes through which it is sustained and perpetuated. Such informal exchange, mutual engagement, and reciprocity characterises the sense in which relationships and understandings are structured by the way artists offer each other support. Although, self-organising could also be characterised as subjective empowerment, since the emphasis is on self (even when located within the social relationships of communities, collaborative and collective practice). Ultimately though we are talking about a complex of artists fulfilling their own professional needs and interlocking with multiple communities. At the same time though they are promoting interdependence by developing social capital, the very fabric of our connections with each other.

When thinking about the informal relations and understandings that develop in mutual engagement under the rubric of community it also important to acknowledge that every community contains a multiplicity of interlocking communities, interacting within complex and continually changing networks. They can be thought of as communities-of-communities.

18,444 Comments